Quantitatively, Japanese sake can be described using several parameters. First is, naturally, its Alcohol By Volume (ABV).

It’s typically around 16% but can be plus/minus 3-4%. As with any other alcoholic drink, the higher the number, the bigger the kick.

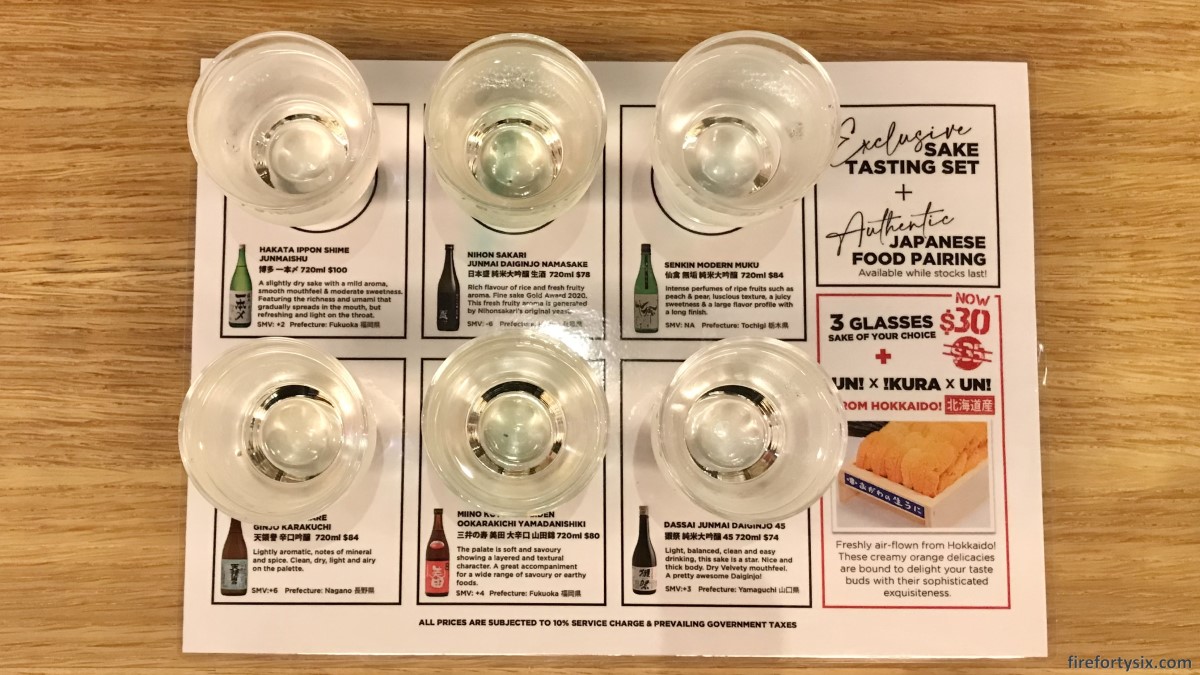

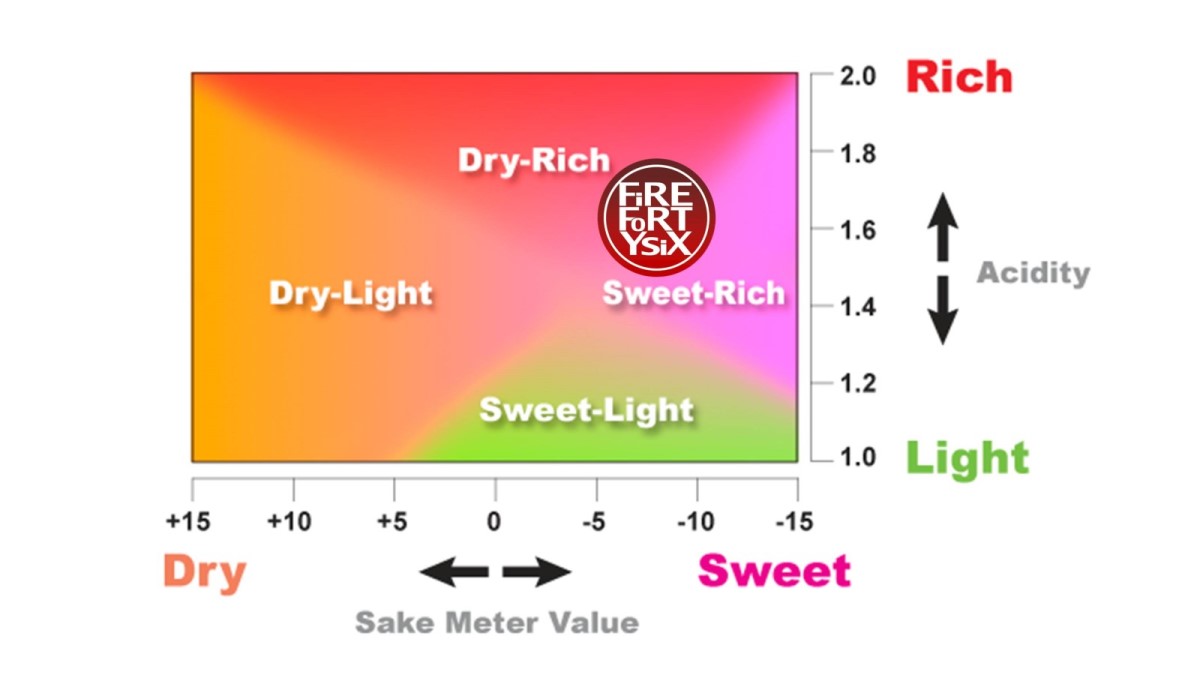

Next come measurements such as Sake Meter Value (SMV) and Acidity.

The former provides a rough indication of whether a sake will taste sweet (-ve SMV) or dry (+ve SMV), while the latter gives an idea of its richness (high acidity) or lightness (low acidity).

But probably the most important number that a sake brewer will print on each bottle’s label is its Rice Polishing Ratio (RPR), or Seimaibuai (精米歩合).

It refers to the percentage of the rice grain that remains, after its outer layers have been polished away. A rice polishing ratio of 60% means that 40% has been removed before undergoing fermentation.

Generally speaking, the lower the number, the more delicate and “refined” the sake, which typically translates to a higher price. Which makes economic sense, since removing more rice means there’s less of it to convert into alcohol.

Over the years, I believe I’ve sampled enough sake to make a somewhat educated guess of any particular bottle’s flavour profile, purely based on these quantitative measures.

Of course, there’s more to it than just numbers printed on a bottle.

Different breweries in different cities using different yeasts and rice varietals can result in nihonshu that’s vastly different, even when ABV, SMV, Acidity and RPR are identical.

So, what’s the best way to figure out the specific impact of a sake’s rice polishing ratio on how it tastes? The scientific approach would be to change the values of only one variable, while keeping everything else constant.

If only there was a Japanese brewery that made the exact same sake, the exact same way but changed only the seimaibuai for different bottles.

Then, I could simply order a flight of this hypothetical range of sakes, and conduct a taste test across various rice polishing ratios.

It turns out that such a brewery actually exists, and such a sake flight is available at a yakitori bar that was only a 15 minute walk from our hotel in Kyoto.

Yanagi Koji (柳小路) is a quaint little street off the main downtown stretch, peppered with a small selection of restaurants and bars.

When it comes to the number and variety of F&B options, it pales in comparison to Pontocho Alley just down the road. But it is home to Yanagi Koji Taka (柳小路TAKA), a compact yakitori bar with standing counter “seats”.

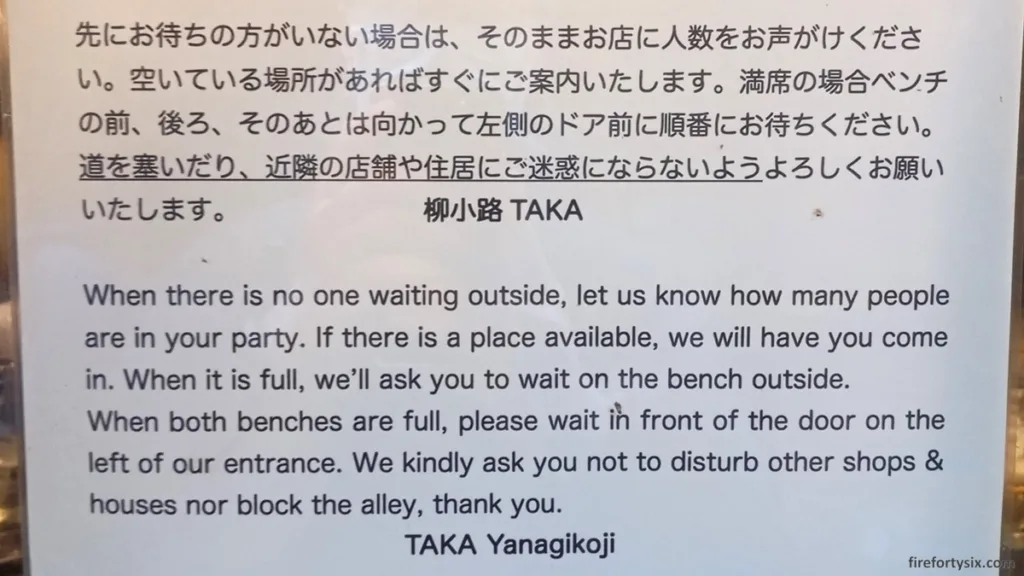

Reservations are not accepted, and there’s a verbose sign (in both Japanese and English) pasted at the entrance that says, “Tell us how many people, then wait outside until we call you.”

But since this is Japan, it was written in an infinitely more polite, and roundabout, way.

It was full when we got there, but we didn’t have to wait long before a party left. They were visibly tipsy, slightly wobbly but clearly happy, all good signs of an enjoyable night out.

Our assigned spot was right in front of the yakitori grill. Smokey, but otherwise the perfect place to observe the cooking action. Water was self-service and came in a chunky 1.8 litre glass bottle.

Good thing that we can read a bit of kanji, because the label stated that it was the same water used to brew their sake with. I didn’t recognise the specific location, but it was some underground water from some lake near some mountain.

I suppose I could wax lyrical about how soft and supple it was, or how clean and crisp it felt on the tongue. But honestly, to me, it just tasted like water.

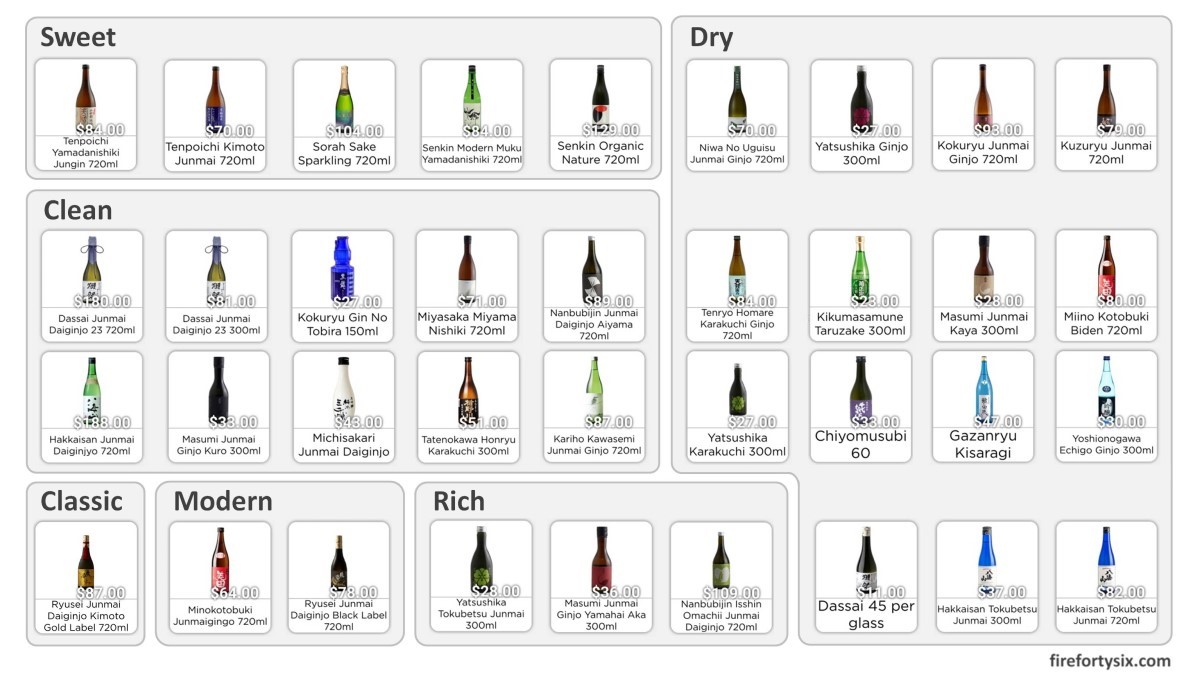

The drink menu was pasted on the wall, and contained all the usual suspects. It was written in Japanese, but the Google Translate mobile app came to the rescue.

All the usual suspects were there, including nama birus, shochus, highballs, whiskeys, fruit sours, cocktails, wines and a smattering of non-alcoholic options.

Plus, of course, 日本酒 or nihonshu, a.k.a. Japanese sake.

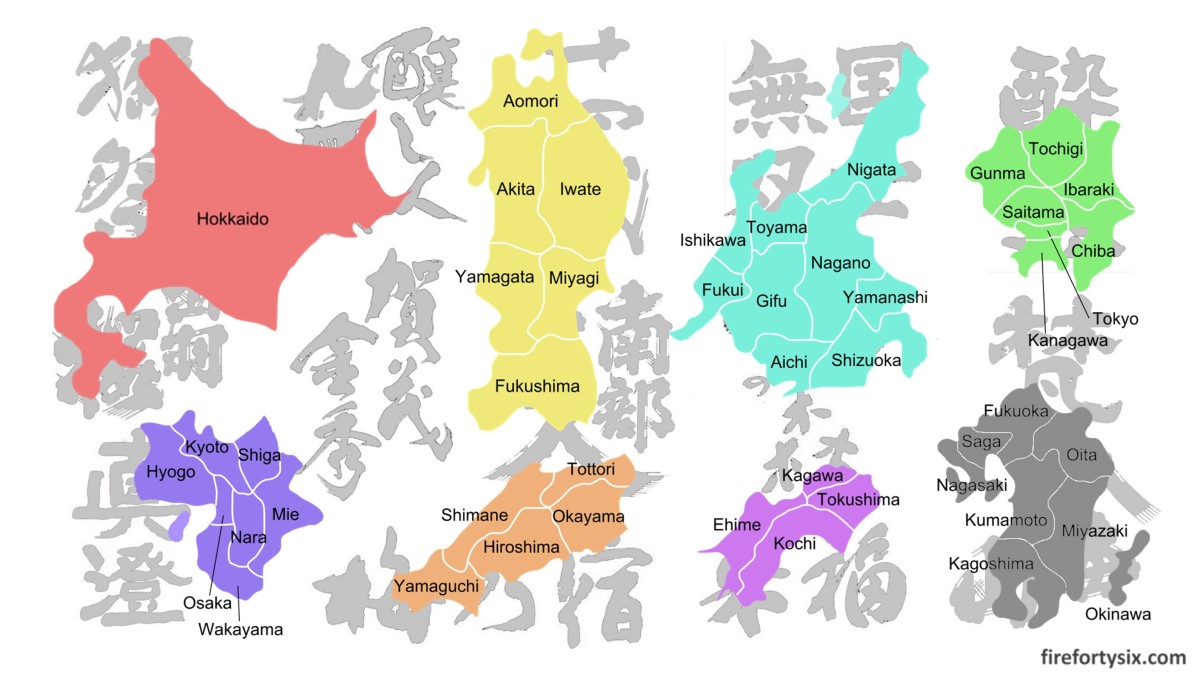

Unlike other typical salaryman sake bars, where they would offer a wide selection, here, there was just one brand from just one brewery — Kin Kame (金亀) by Okamura Honke (岡村本家) in Shiga prefecture (滋賀県).

But they compensated for the lack in variety by offering the same sake in nine different rice polishing ratios. Starting from 20% and ending at 100% (i.e. not polished at all), in 10% increments.

As much as I would have liked to order one of each, it was probably too much for my liver to handle. Wisely, I ordered the 7種テイスティング ¥1,500 tasting flight, which was why we were there in the first place.

It arrived in a custom-made wooden serving block, with seven cutouts that fit seven shot glasses. Each of them were two-thirds filled and contained nihonshu with RPR from 40% to 100%, again in 10% increments.

A helpful laminated guide was laid out under the block, indicating the seimaibuai for each of the glasses. Google Translate didn’t have to step in this time, as English explanations were provided.

We were advised to start from the left (40%) and slowly work towards the right (100%).

The 40% 大吟醸 (daiginjo) was smooth, very drinkable and similar to what we normally drink. It couldn’t compare to our favourite junmai daiginjos like the Keigetsu CEL24, Born Gold or Kuheiji Eau du Désir, but it was decent enough.

I expected the 50% daiginjo to taste quite similar, but it was noticeably drier than the 40%. Which ran counter to the provided chart, since it indicated less dryness and more sweetness as seimaibuai increased.

The 60% 吟醸 (ginjo) tasted nicer than the 50%, but didn’t match the smoothness of the 40%. Cost/performance-wise though, it was the best among the three.

Once I was done with the flight, it was the one I would consider re-ordering. The Wife had been tasting the sakes in parallel, and she agreed with my assessment.

70% RPR was the highest we’ve ever gone in a sake. In fact, one of our favourite sakes is the Kaze no Mori Alpha 1 and it sports the same ratio. However, unlike the bright and dynamic Alpha 1, this Kin Kame was bland and had no character.

After that, it was all unchartered territory.

We took the first sip of our very first 80% RPR sake, and it tasted… weird? but in an interesting way. It was so alien that I couldn’t find an analogy for what I was experiencing.

The 90% had a similar profile and remained strange, but since there was no longer the element of surprise, it tasted much less interesting.

Finally, we reached the end of our journey.

100% unadulterated, whole brown rice with nothing removed. And it was really way out there, like way, way out there. It was supposed to be the sweetest of the lot, but it tasted almost sour.

In my mind, it was definitely not sake; not even close. There’s a reason why 100% RPR sakes are uncommon, and I now understood why that was the case.

It’s like what they say, “You have to experience bitterness to appreciate sweetness.” If we hadn’t done this experiment, we would never have truly understood why popular sakes have RPRs of 70% or less.

Well, now we know.

If you want to find out for yourself and happen to be in Kyoto, you know where to go.