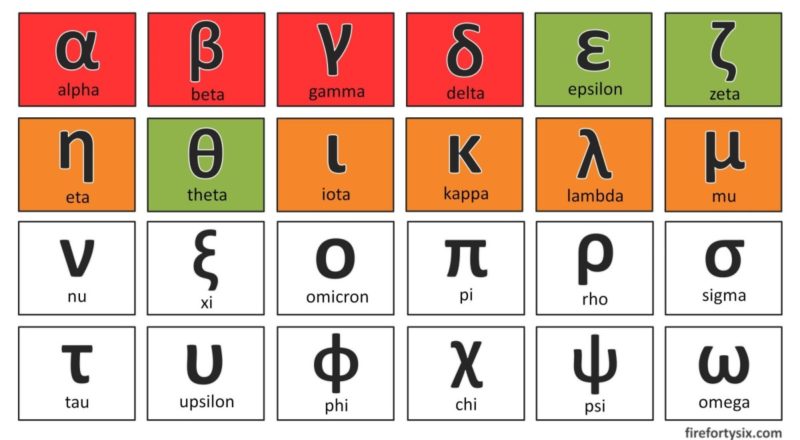

The World Health Organisation (WHO) decided in May 2021 to name Covid-19 variants using the Greek alphabet, which contains 24 letters starting with alpha (α) and ending with omega (ω). And so far, exactly half of them have been used.

There are currently 4 Variants of Concern (alpha, beta, gamma, delta), 5 Variants of Interest (eta, iota, kappa, lambda, mu) and 3 former Variants of Interest (epsilon, zeta, theta).

Given the rate at which mutations are happening, it’s almost a certainty that the remaining 12 letters will be utilised at some point in time. Let’s just hope that it doesn’t happen too quickly.

Science recently published an article titled “Evolving Threat: New variants have changed the face of the pandemic. What will the virus do next?” which I found to be quite informative. It’s not a scientific paper and takes around 15 minutes (give or take) to read through. Here are some highlights which caught my attention.

Probably the most eye-catching visual in the article is the dot plot below that shows how mutations have spawned the various variants since December 2019.

It looks quite intimidating as it stands, but even this plot represents an extremely small percentage of the more than 2 million mutations that have been detected. Just take a moment to look at the plot again, and let the sheer magnitude sink in.

As a sign of how quickly dangerous variants are popping up, you’ll notice that the caption says “four variants of interest”, which is already obsolete as the fifth variant of interest (mu) has already been named by the WHO.

The four variants of concern have different levels of transmissibility, with alpha driving the global surge early this year and delta causing the most damage currently. The article notes that alpha was 50% more transmissible than previous variants, with delta being 40-60% more transmissible than alpha.

Vaccination programs are in full-swing across many countries, especially those in the developed world that have ready access to vaccines. But a key concern of health authorities is the ever-present danger of vaccine breakthrough and immune escape.

"From the start of the pandemic, researchers have worried about a third type of viral change, perhaps the most unsettling of all: that SARS-CoV-2 might evolve to evade immunity triggered by natural infections or vaccines.

Already, several variants have emerged sporting changes in the surface of the spike protein that make it less easily recognized by antibodies. But although news of these variants has caused widespread fear, their impact has so far been limited."One way that researchers are studying this effect is through the use of “antigenic maps” as explained in the graphic below. It was quite disconcerting to see how far away the newer variants have been drifting from the original virus strain.

But this fear was moderated somewhat by highlighting how a Hepatitis B variant managed to evade existing vaccines in 2000 but didn’t trigger a widespread pandemic, because the mutation that allowed it to achieve vaccine breakthrough also reduced its transmissibility.

"Immune escape is so worrying because it could force humanity to update its vaccines continually, as happens for flu. Yet the vaccines against many other diseases—measles, polio, and yellow fever, for example—have remained effective for decades without updates, even in the rare cases where immune-evading variants appeared.

'There was big alarm around 2000 that maybe we’d need to replace the hepatitis B vaccines,' because an escape variant had popped up, Read says. But the variant has not spread around the world: It is able to infect close contacts of an infected person, but then peters out. The virus apparently faces a trade-off between transmissibility and immune escape. Such trade-offs likely exist for SARS-CoV-2 as well." So, where do we go from here?

It’s becoming clear that achieving herd immunity on a global level is near impossible, and even attaining it on a country-wide level is highly improbable. Covid-19 will not magically disappear one day, but will instead become endemic to the human population.

I have come to terms with the fact that I will catch Covid-19 one day, like I have caught many different strains of the flu, numerous times in the past.

Mutations will continue to occur, and new variants will continue to surface. But hopefully, as the virus evolves, there will also be a trade-off between transmissibility and potency, resulting in variants that become increasingly less lethal.

While many will continue to be infected, few will develop serious symptoms and even fewer will unfortunately perish.

It’s not an ideal outcome, but it’s probably the least bad option. Given how long and how furious this virus has been raging around the world, this may be as good as it gets, as we slowly learn to live with Covid-19.